Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S.

Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014

1848 The first women’s rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women’s rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women.

1850 The first National Women’s Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860.

1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States”

1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution.

Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and others form the American Woman Suffrage Association, which focuses exclusively on gaining voting rights for women through the individual state constitutions.

1872 Susan B. Anthony arrested for voting for Ulysses S. Grant in the presidential election.

1878 The Women’s Suffrage Amendment is first introduced to congress.

1890 The National Women Suffrage Association and the American Women Suffrage Association merge to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). As the movement’s mainstream organization, NAWSA wages state-by-state campaigns to obtain voting rights for women.

1893 Colorado is the first state to adopt an amendment granting women the right to vote.

1896 The National Association of Colored Women is formed, bringing together more than 100 black women’s clubs. Leaders in the black women’s club movement include Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Mary Church Terrell, and Anna Julia Cooper.

1913 Alice Paul and Lucy Burns formed the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage. Their focus is lobbying for a constitutional amendment to secure the right to vote for women. The group is later renamed the National Women’s Party. Members picket the White House and practice other forms of civil disobedience.

1916 Alice Paul and her colleagues form the National Woman’s Party (NWP) and began introducing some of the methods used by the suffrage movement in Britain. Tactics included demonstrations, parades, mass meetings & picketing the White House over the refusal of President Woodrow Wilson and other incumbent Democrats to actively support the Suffrage Amendment.

1917 In July picketers were arrested on charges of “obstructing traffic.” including Paul. She and others were convicted and incarcerated at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia. While imprisoned, Alice Paul began a hunger strike.

1918 In January, after much bad press about the treatment of Alice Paul and the imprisoned women, President Wilson announced that women’s suffrage was urgently needed as a “war measure.”

1919 The federal woman suffrage amendment, originally written by Susan B. Anthony and introduced in Congress in 1878, is passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate. It is then sent to the states for ratification.

August 26 1920 The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, granting women the right to vote, is signed into law.

Center for American Women and Politics Rutgers

The State University of New Jersey 191 Ryders Lane New Brunswick

New Jersey 08901-8557

tag.rutgers.edu tag@eagleton.rutgers.edu

732-932-9384 Fax: 732-932-6778

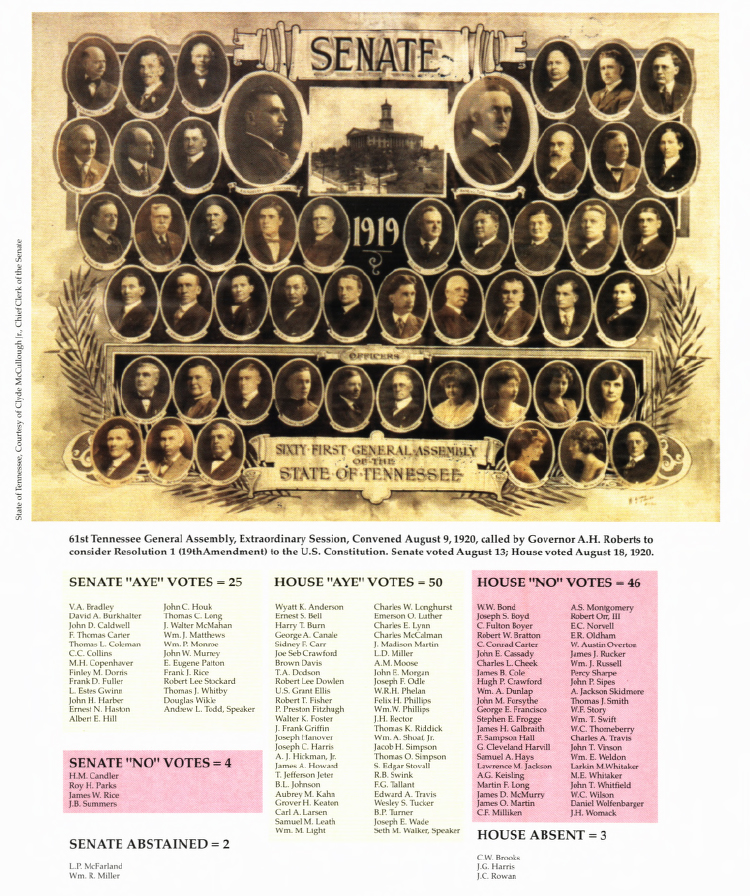

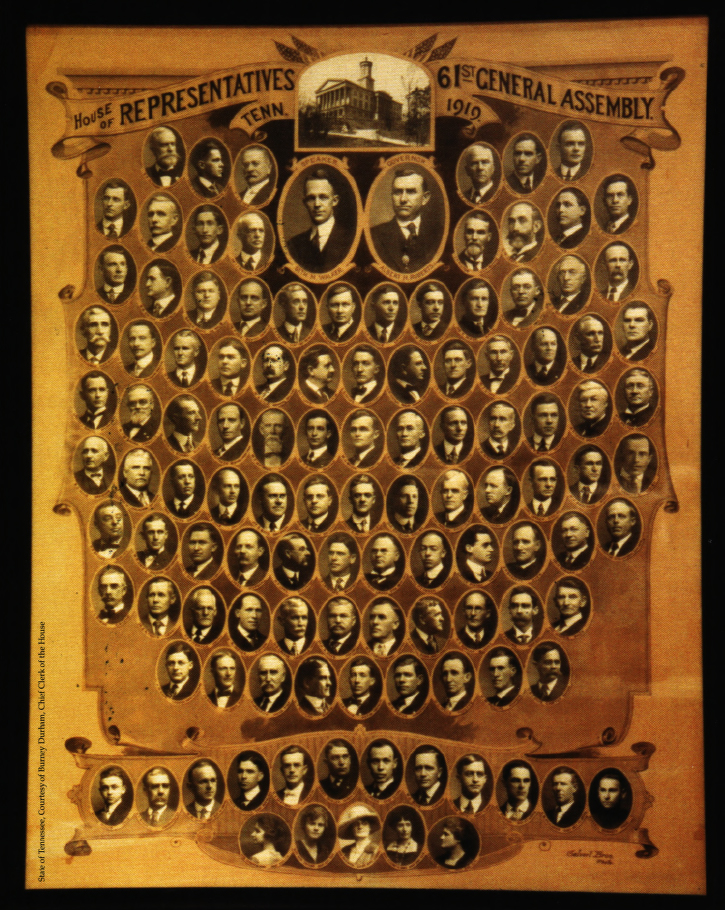

The Men Who Made it Happen in Tennessee

Tennessee As “The Perfect 36”

Suffragists had to win in no fewer than 36 legislatures, while their opponents, the entrenched and well-heeled Antis, could kill the amendment by squashing it in just 13 legislatures. Behind the Antis’ formally organized battalions — a National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (for ladies) and the American Constitutional League (for gentlemen) — stood the suffragists’ real and most powerful enemies, a shadowy conglomerate of special interests referred to as the whiskey ring, the railroad trust, and the manufacturers’ lobby.

From June 10, 1919, until March 10, 1920, there were 34 state ratifications. On March 22, 1920, the Washington state legislature was called into special session and unanimously completed ratification #35. Where was #36? With final victory so amazingly and tantalizingly close, the ratification campaign stalled. Six states, all Southern, had already rejected the amendment. Only seven states had not yet acted, and three of these – Florida, Louisiana, and North Carolina – were also from the Deep and Democratic South. No chance there where memories of federally-controlled elections during the dark days of Reconstruction still rankled, and the 19th Amendment, with its Section 2 granting enforcement powers to Congress, was anathema. There was no hope in Connecticut or Vermont.

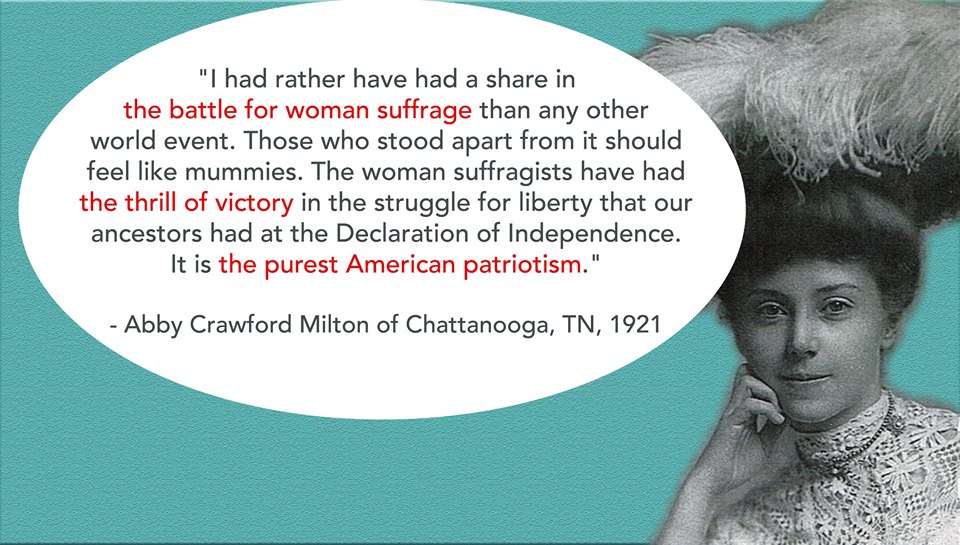

It fell to Tennessee, a border state with well-organized pro-suffrage groups – National American Woman Suffrage Association and National Woman’s Party stalwarts — and anti-suffrage factions, to become “The Perfect 36.” The reluctant governor, A.H. Roberts, conveniently called a special session for August 9, 1920, after his party primary. After extensive heated debate and parliamentary maneuverings, the state Senate concurred 25-4. The House vote was a cliff-hanger. It passed 50-46 on August 18, 1920, and survived constitutional challenges so that Tennessee’s ratification made votes for women the law of the land.

April 5 Marks Anniversary of Legislation Making Women Eligible to Hold Public Office In Tennessee

In 1893, the Tennessee Supreme Court declared:

“By the English or common law, no woman, under the dignity of a queen, can take part in the government of the State, and they can hold no offices except parish offices.

Although a woman may be a citizen, she is not entitled, by virtue of her citizenship, to take any part in the government, either as a voter or as an officer, independent of legislation conferring such rights upon her.

It follows that unless there is some constitutional or legislative provision enabling her to hold office, she is not eligible to the same.“

In short, although a woman was a citizen of the state, she had no right to vote or hold any elected office.

Twenty-six years later, on April 17, 1919, Governor A. H. Roberts signed into law Public Chapter 139, an act granting women the right to vote for electors of President and Vice President of the United States, and for municipal officers. Women in Tennessee could now vote in most elections, but the bar to holding public office remained.

In August 1920, Tennessee became the 36th State to ratify the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution; women throughout the country were then able to vote in the November 1920 Presidential election.

In a special election held in January 1921 in Tennessee to fill the vacancy caused by the death in office of Senator J. Parks Worley, his widow, Anna Lee Keys Worley, was elected by the voters of Sullivan and Hawkins counties as the first female member of any southern state legislature.

On March 10, Senator Anna Lee Keys Worley introduced 1921 Senate Bill 737, “an act to make women eligible to hold public office in Tennessee.”

It passed both houses and was signed into law by Governor A. A. Taylor, making it 1921 Public Chapter 95, on April 5, 1921.